Introducing Semantic Distance

A metric to measure your agentic back pressure

February 18, 2026

This week Moss and Geoffrey Huntley (creator of the Ralph loop) wrote about the importance of automated feedback as back pressure for agents. It’s the idea that the controls you build around and for an agent determines how far it can run autonomously. If you want to deep dive in the topic, you should check this session by Dex and Vaibhav.

This post focuses on how to build a metric to control back pressure; we will frame it with two basic questions:

- The When question: When should a human step in? The later, the better.

- The What question: What should the human look at? The less, the better.

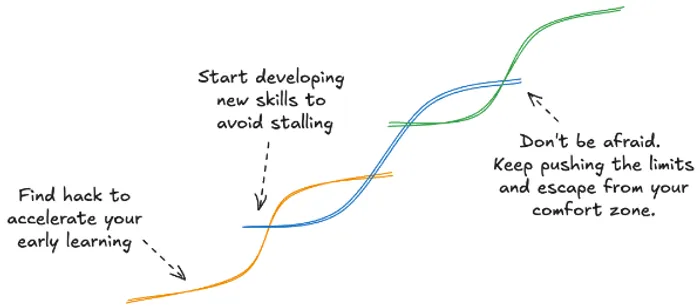

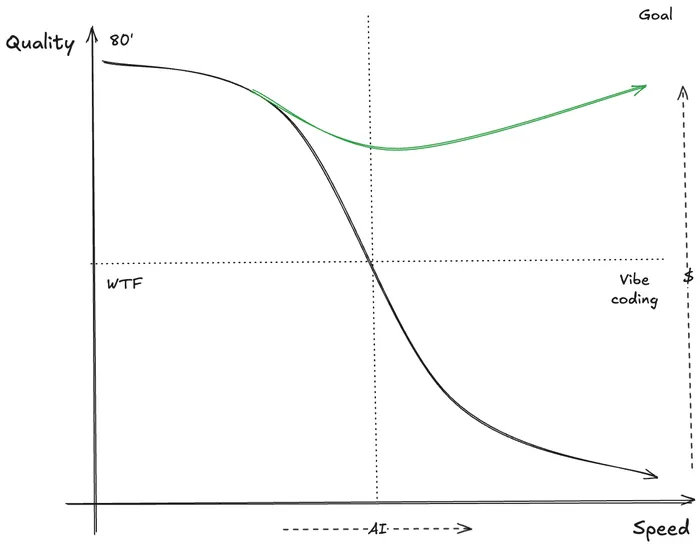

AI’s ultimate goal is to scale to levels unimaginable before. Each time you reduce the gap of what and when, you should naturally go faster due to the increase of time. Hence what and when will naturally go up again. It’s an optimization game.

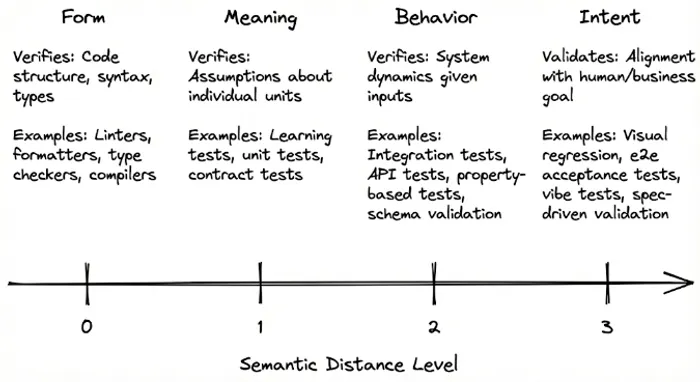

Now that we are aligned that back pressure is the key to control what and when, we might want to bisect how the feedback is structured. This is, understanding the different levels of back pressure we can differentiate, which ones should be automated and which ones should be part of the human loop. I decided to call it semantic distance.

It’s a simple scale that describes the different types of backpressure measures you can set to your coding agent to be able to reduce what and when. But, as usual, it comes with tradeoffs.

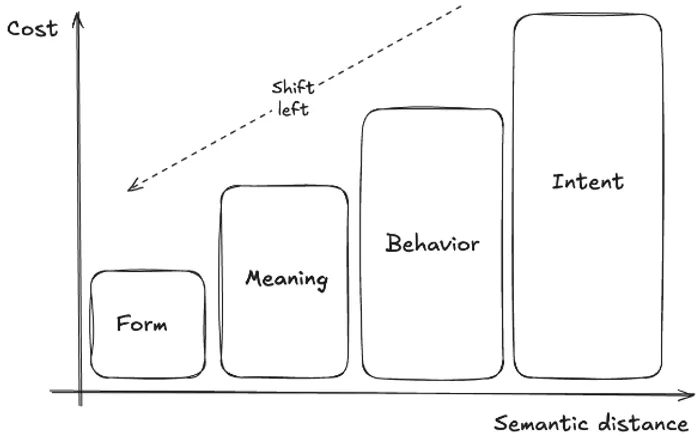

First of all, as you go up in the semantic distance level, the cost of those measures increases. It increases in complexity (type checking is easier than writing unit tests), and in costs (running an API check is cheaper than having a Playwright E2E suite run at scale). Nevertheless, the cost of a human stepping in at a low level is too great to pay.

But the cost of not having each level increases even faster. A missing import caught at Form costs milliseconds. The same bug caught at Meaning costs a test cycle. Caught at Behavior, it’s a failed deployment. Caught only at Intent (or worse, in production) it’s a war room. The framework isn’t about spending more on testing. It’s about spending in the right place to avoid paying exponentially more later. This optimization process is often referred to as shift left.

Instead of focusing on the examples, I want to reason around the goal or each level, as understanding them will automatically yield what the concrete examples should be in each team.

We will be using an example in which an agent generates a new /users/:id/settings endpoint.

Form

The smallest unit of verification for an agent

The first level is Form. It’s the most basic form, which should never be even thought of by a human. No code should be committed without passing these primal checks.

E.g. The linter flags an unused import the agent left behind. The type checker catches a string passed where the schema expects boolean. Cost: milliseconds, zero human involvement. Another example is using codemods to upgrade client code on API changes.

Meaning

Agents proof of work

The second one is Meaning. This is where the basic building blocks of your code are verified. I like to think of these as the proof of work for the agents. Any new code added should have its basic unit tests. Each external dependency should consider its applicable learning tests that make you feel safe when upgrading. Each service communication layer should have a way to ensure compatibility. This is the core trust layer, and it should be append-only. You should only remove a meaning check if you remove its associated code. Pushing should be blocked if not passing, and a new delta should be required on additions.

E.g. A learning test reveals that the ORM’s

.update()method doesn’t do a partial merge, rather it replaces the entire record. The agent assumed patch semantics but the library has put semantics. A unit test catches that the validation logic rejects valid timezone strings. Cost: seconds, still no human.

Behavior

An agent should have all the necessary tools to be able to run behavior tests, and these should be part of your plans.

The third is Behavior. This is where your business logic starts to come into play. The first two levels are generally business logic agnostic. The behavior checks go one step further, they assume that your application or services are alive. This is historically what some folks did manually in their local machines using Postman, or running custom scripts to test interactions. The agent must have a way to do it on their own. This is the first difference with how things were done before AI. The agent should have all the necessary tools to be able to run behavior tests, and these should be part of your plans / specs. If the background agent you are using is not able to use these tools, you either won’t scale, or just open the door for the next war-room. Coding agents enable you to build these tools in-house without the time investment that was hard to justify before. Invest in this.

The agent should have all the necessary tools to run behavior tests autonomously. Think of how OpenClaw configures its own environment (installing CLIs, authenticating, updating memory) without human intervention. Your agents need the same self-sufficiency for testing.

In the behavior level you should aim to have specific checks in each non-trivial plan, and during review you (the human) should have easy ways to see and validate what behaviors were checked.

E.g. An integration test hits the running service and discovers the endpoint returns 200 on success instead of the 204 the OpenAPI spec defines. A contract test catches that the response shape doesn’t match what the frontend client expects. Cost: seconds to minutes, still no human.

Intent

Does this change make sense or not? Does the change solve the problem it needs to solve?

The fourth and final level is Intent. This is the most expensive and complex to automate. Not because writing E2E tests is hard (which is not) but because scaling them and making sure they capture the real intent is not trivial. Yet, they surface the most important part of the agentic flow: does this change make sense or not? Does the change solve the problem it needs to solve?

You may want to check Validation, not verification which focuses on this specific level.

These might vary a lot from business to business. If you do not have a UI, your intent might be if the new CLI can be used as a user would, if you are a voice agent then maybe you care about the new branches the change created, etc. This is what the human would actually validate. For that, as with the previous level, being able to see what it checked is critical.

In some cases, the infrastructure required to do so is hard and expensive (e.g. ephemeral environments, production database forks, etc.) but if you do not solve that, you will never be able to know if the change is right. No, not even if Opus 13.7 ships. Think about it, how do you know that the Principal that just joined your startup actually understands what it means to do X or Y on the platform? It does not matter if it’s the best in the world, if the intent is not clear and tested, I’m afraid you are playing roulette.

E.g. An e2e test simulates a user changing their notification preferences and confirms the change persists across sessions. A visual regression test confirms the settings page renders correctly. Cost: minutes, and this is where the human reviews what was checked. The agent self-corrected three times before a human ever looked at the PR. That’s the point.

So, how do you actually use this?

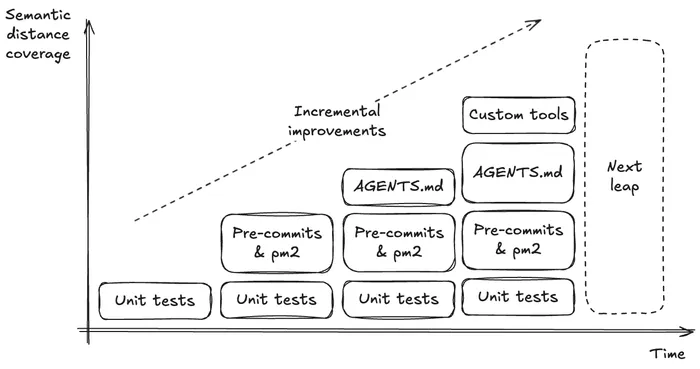

Where to start

This one is easy. You should start from the lowest and start going up. If you do not enforce basic Form and Meaning levels, you should immediately. Having those failing or requiring human review to enforce them is a huge waste of time. Especially due to how tools like Github are built, in which you spend a lot of time clicking around to understand what is failing, plus the waiting times (to not talk about billed minutes).

Once you have those controlled and enforced, you should start working on Meaning. Start small. When a new AI PR comes in, think of the basic checks you would need to feel safe. What would be the most basic stuff you would explain to a new intern joining the team? Figure out those and spend an afternoon building a small script folder (I recommend using bun for these) and have some easy to use CLI scripts to check your API, setup pm2 and let the agent control it and see the logs, update your AGENTS.md file with pointers and examples to those, etc.

Once you have this, you can start adding Behavior checks as part of the plans or specs. You may even start to let the agent propose these. As you automate more and more behavior tests, you’ll naturally start poking into the Intent. I saw Claude Code naturally researching and proposing manual verifications of the changes. Invest in ways for the agent to search for information about your business, gauge it to make you questions when needed.

When working on bigger projects and non trivial changes, you will start by naturally pulling locally to do some of these. Aim to reduce the times you do that. Remember your recurrent questions or asks during reviews, find ways to automate those. You are the agent’s most useful feedback loop.

What changes in review

This correlates directly with how up you are in the semantic levels. When you are in low levels, you will be forced to review in more detail, potentially even checking line by line. As you progress in it, the code starts to become more and more of an implementation detail, and what you need is to clearly see what was the thought process of the agent, what behavior checks it performed, what tradeoffs it took and why, and the intents it verified. All these should be easy to check and to give feedback on.

The goal is that the answer to this question is simply an executive summary. If you are stuck reviewing code, go back to the previous question and check where you are in the levels. Move the lever forward, and try to answer again.

These two questions are the done conditions of your human loop. Each time you close the gap on one, you should naturally go faster. Hence both will naturally go up again. It’s an optimization game. It’s not the same being a team of 50 to being a team of 100, or 200.

Where this is headed

The payoff of investing into higher quality testing is growing massively, and an increasing part of engineering will involve designing and building back pressure in order to scale the rate of contributions from agents exponentially. Every level of semantic distance you automate is a multiplier on how much your team can ship without increasing headcount or review load.

History is a powerful source of knowledge, and we should use it. Processes that scaled teams from 10 to 50 to 200 already exist: code owners, launch docs, RFCs. The difference is that now the “new hires” are agents, and the onboarding process is your test suite.

It’s unclear what will happen in the next months, but what is clear is that what got us here, won’t get us there. A lot of the answers to the new questions that arise today, lay in some way or another in a solution from the past.